What is Vascular Aging?

December 17, 2019

How To Accurately Measure Blood Pressure at Home

December 21, 2022Vascular Age: How Old Are You Really? It’s All in the Pulse

“A man is only as old as his arteries.”

At Raffaele Medical, we are reminded of Osler’s remark with every new patient evaluation because it’s cardiovascular health that many people think about most when they’re concerned about living—and staying younger—longer. As its name suggests, the cardiovascular system (CVS) has two vital components; most people are preoccupied with only the cardio when it’s the vascular they should be watching. Keep the blood vessels healthy, and the heart will follow suit.

WHAT’S THE NUMBER ONE RISK FOR CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE?

We know that heart disease and stroke—the principal components of cardiovascular disease—are the first and fifth leading causes of death, respectively, in the United States, accounting for more than 40 percent of all deaths.1 (Cancer is second.) What do you suppose is the number one factor that puts a person at risk of dying of cardiovascular disease or of facing a serious deterioration in quality of life as a result? Answers typically involve the usual suspects such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, family history of ischemic heart disease, obesity, or smoking. A more finely tuned response may be elevated blood levels of homocysteine,2 ApoB,3 or short telomeres,4 all of which have been linked to a heightened risk of premature coronary artery disease and stroke.

All these factors are important elements of cardiovascular disease risk, but if you voted for any of them for the title of Leading Risk Factor, you’d be wrong. In fact, the greatest risk factor of all for cardiovascular disease is age. If you’re twenty-five, you can have high cholesterol, smoke two packs a day and have lost your father to a heart attack at forty-five—and still not have any of the common cardiovascular diseases. But if you’re seventy-five, you can have none of these risk factors and still have an increased chance of having a heart attack or stroke. While these diseases are extremely rare in people under twenty-five and still uncommon under forty, they comprise the number one cause of death in people older than sixty-five. What’s more, your risk of heart attack is six-fold higher in your eighties than in your forties, and your risk of stroke is ten times higher. For the vast range of people between these ages, the more risk factors you have, the higher your chances of having cardiovascular disease earlier. The risks progressively increase with each passing year.

We will all die of cardiovascular disease—unless something else kills us first. Even if you manage to evade every kind of cancer and the rarest diseases, if you never get diabetes or kidney disease or any other condition that causes natural death, your cardiovascular system will eventually do you in. That’s why the medical establishment and the pharmaceutical and fitness industries have put so much time, effort, and money into risk factor reduction by trying to alter people’s diets and lifestyles, and by developing drugs and methods to help them lose weight and reduce cholesterol. But until the last decade or so, what’s been ignored is the bedrock upon which all these common risk factors wreak their havoc, and that is the aging process.

This philosophy is echoed in several review publications that discuss the concept of vascular or arterial age, which seeks to measure the effect that an individual’s particular constellation of risk factors has on the actual structure and functioning of the vascular system. Biological age is a measure of the effect of all the risk factors a person’s cardiovascular system (CVS) has endured to date.5 A biological age biomarker is one that describes how far from optimal structure and function a person’s cardiovascular system has diverged.6

THE LESS APPRECIATED FUNCTION OF THE VASCULAR SYSTEM

The best candidates for this biomarker of vascular age can be categorized into two major functions of the vascular system they measure: the conduit and the cushioning.

When most patients and clinicians think of the aging and deterioration of the CVS, they think about arterial blockage from plaque accumulation called atherosclerosis, which is the leading cause of heart attacks and ischemic stroke. This thickening of the arteries increases linearly by 0.005 mm per year in the average healthy person, as measured by carotid intima-medial thickness.7 Once 1.1 mm is reached, atherosclerosis is diagnosed. This damage affects the conduit function of the arterial tree, which ensures the delivery of blood to tissues that bring oxygen and nutrients. This type of damage leads to angina, heart attacks, and strokes.

The less appreciated function of the arterial tree is the cushioning element that dampens the cardiac cycle’s damaging pulsations on the fragile small arteries and capillary beds of the major organ systems. This cushion is lost as the arterial system gets progressively stiffer through degradation of endothelial function, collagen crosslinking, and loss of elastin in the large arteries, resulting in a tsunami of heart and kidney failure, even in patients without significant atherosclerosis.8 Gradual loss of this function is what we refer to as hardening of the arteries, or arteriosclerosis, which is more of an intrinsic arterial aging process. While it can be crudely measured by conventional brachial blood pressure, a more sensitive and predictive measure is central arterial stiffness, which affects both the heart’s structure and function. It is a major cause of high blood pressure in older people and a precursor to atherosclerosis. Stiffer arteries are more prone to accumulate deposits of cholesterol, white blood cells, and clotting factors that make the interior of the artery wall thick and irregular.

While everyone’s arteries stiffen with age, how much they do and how fast can vary widely. So, it stands to reason that the degree of stiffness is a key factor in determining whether it will lead to cardiovascular disease and when. And if we can take an accurate measure of that process, we have an invaluable biomarker of aging, one that is routinely monitored at Raffaele Medical: arterial pulse pressure. This biomarker is a measure of the speed and the size of the pressure wave as it travels from the left ventricle through the aorta, and the role played by what is called the reflected wave, which returns after the initial wave reaches the small arterioles. The speed of this reflected wave is determined by the stiffness of the arteries along which they travel: The stiffer the arteries, the more quickly the wave travels out and the earlier the reflected wave arrives back at the heart.

“While it can be crudely measured by conventional brachial blood pressure, a more sensitive and predictive measure is central arterial stiffness, which affects both the heart’s structure and function.”

At Raffaele Medical, we accurately and noninvasively measure infinitesimal changes in arterial stiffness using aortic pulse wave analysis (APWA) obtained from sensors in an arm cuff that only looks like a standard brachial pressure cuff. The computer-assisted technique determines the speed of pulse and size of these waves, yielding a measurement of the stiffness of the aorta and the arterial tree. The accuracy of these waveform measurements has been validated against those gleaned from placing catheters inside the aorta.

The arterial waveform reveals two components: The first is large artery stiffness measured by pulse wave velocity (PWV), where a 1m/sec increase is associated with a 15 percent increase in cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality after adjusting for multiple risk factors, including age.9 The second component is peripheral artery tone, which can be directly measured by flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) and is a marker of endothelial function. Tone is increased due to decreasing levels of nitric oxide (NO) known to occur with age and is accelerated by many traditional CVD risk factors as well as increased oxidative stress and inflammation.10

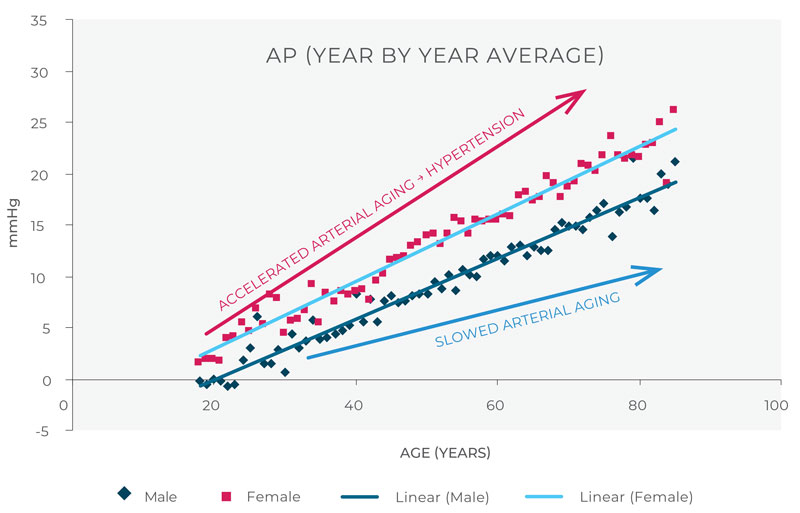

Integrating the change in pulse wave velocity with a measurement of endothelial function tells us how much overall work the reflected wave is causing the left ventricle to do while pumping against this augmentation pressure (AP). A number of studies have established a close correlation between AP and age with a linear increase of 0.25 mm (0-20 Hg per year from twenty to ninety years old) in the absence of brachial cuff-determined hypertension.11 When looked at through the lens of AP, essential hypertension is simply accelerated arterial aging.

This makes AP an excellent biomarker of arterial health and of overall aging, providing a way for us to measure the changing stiffness of the arteries to catch subclinical cardiovascular dysfunction well in advance of conventional methods. Additionally, AP is determined by processes that are reversible, making it a very useful biomarker to test if a given treatment strategy is having a positive effect, whether through lifestyle modifications such as increasing aerobic exercise and lowering stress, supplementing diminishing supplies of NO through beetroot extract, hormone therapy, or through targeted pharmaceuticals such as ACE-I, 12 and more. Pharmaceutical companies are actively looking for drugs to both prevent and dissolve the collagen crosslinking that causes the large artery component of arterial stiffness.13

WHAT’S IN A NUMBER? THE KEY TO BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION

Now that we have introduced you to an accurate and highly validated way to measure vascular age, let’s look at how we use it at Raffaele Medical. All patients get a baseline vascular reference age, which we have termed CardioAge because it’s more intuitive for patients. If a patient is hypertensive at baseline, then their CardioAge will automatically be ninety because those who meet the blood pressure (BP) criteria of hypertension invariably have central arterial stiffness (an AP) higher than the average non-hypertensive ninety-year-old. We find this motivates them to take their antihypertensive more assiduously because it is a less abstract concept than cuff BP. And once they’re on effective therapy, their CardioAge often plummets to that of a much younger person, giving them objective evidence that their compliance has meaningful effects.

ARTERIAL STIFFNESS CHANGE WITH AGE: R-0.7

Dr. Joseph Raffaele provides scientifically-based treatment programs targeting biomarkers of healthy aging derived from decades of research and experience in longevity medicine. He is also the co-founder of PhysioAge Health Analytics.

REFERENCES

- Heron M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep Cent Dis Control Prev Natl Cent Health Stat Natl Vital Stat Syst. 2021 May;70(4):1–115.

- Peng H, Man C, Xu J, Fan Y. Elevated homocysteine levels and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2015 Jan;16(1):78–86.

- Benderly M, Boyko V, Goldbourt U. Apolipoproteins and longterm prognosis in coronary heart disease patients. Am Heart J. 2009 Jan;157(1):103–10.

- Telomeres Mendelian Randomization Collaboration, Haycock PC, Burgess S, Nounu A, Zheng J, Okoli GN, et al. Association Between Telomere Length and Risk of Cancer and Non-Neoplastic Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017 May 1; 3(5):636–651.

- Thijssen DHJ, Carter SE, Green DJ. Arterial structure and function in vascular aging: are you as old as your arteries? J Physiol. 2016 Apr 15;594(8):2275–84.

- Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003 Jan 7;107(1):139–46.

- van den Munckhof ICL, Jones H, Hopman MTE, de Graaf J, Nyakayiru J, van Dijk B, et al. Relation between age and carotid artery intima‐medial thickness: a systematic review. Clin Cardiol. 2018 May 12;41(5):698–704.

- O’Rourke MF, Hashimoto J. Mechanical factors in arterial aging: a clinical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 Jul 3;50(1):1–13.

- Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Mar 30;55(13):1318–27.

- Taddei S, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Salvetti G, Bernini G, Magagna A, et al. Age-related reduction of NO availability and oxidative stress in humans. Hypertens Dallas Tex 1979. 2001 Aug;38(2):274–9.

- McEniery CM, Yasmin, Hall IR, Qasem A, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR, et al. Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 Nov 1;46(9):1753–60.

- Williams B, Lacy PS, Thom SM, Cruickshank K, Stanton A, Collier D, et al. Differential impact of blood pressure-lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) study. Circulation. 2006 Mar 7;113(9):1213–25.

- Song Q, Liu J, Dong L, Wang X, Zhang X. Novel advances in inhibiting advanced glycation end product formation using natural compounds. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Aug 1;140:111750.